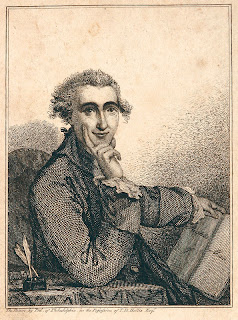

Thomas Paine

"damned be his name,

and lasting his shame"

Post debt ceiling crisis, the U.S. continues to ride a financial roller coaster, and I continue to feel that the actions of the tea party legislators and other strict conservatives and their refusals to compromise were wrong. Still, I hope that the methods these fanatics chose will eventually aid in a positive change. Many people won't agree with my labeling of the tea party as a fanatical group. Well, to me a fanatic is someone who closes his ears to everyone and who refuses to compromise. A fanatic, despite a firestorm of criticism, rolls on as he or she sees fit. Actually, when stated that way, there is the suggestion of nobility in fanaticism.

The anti-war and the civil rights movements were certainly aided by the efforts of fanatics. The loose cannons of the 60's and 70's irritated people but forced them to look at problems they would rather have avoided. Their fanatical acts often kept their causes in the headlines and on the nightly news. As a result the thinking of many Americans, young and old, was altered.

The United States exists in great part because of the mind and pen of my favorite fanatic, Thomas Paine. Not only was Paine a founding father but a founding fanatic, as well. Between 1776 and 1807, he wrote four pamphlets, "Common Sense" in 1776, designed to stir Americans to revolution; "The Crisis" in 1777, to raise the spirits of American soldiers; "The Rights of Man" in 1791 and 1792, in support of the French Revolution and against monarchies; and "The Age of Reason" in 1794, and '95, and 1807, a three part attack on the church of the time. Of Paine's "Common Sense," John Adams wrote, "Without the pen of the author of 'Common Sense,' the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain." His words stirred and moved people and nations. It was Paine who said in "The Crisis," "These are the times that try men's souls." Of the importance of the American revolution to the world, he wrote in "Common Sense," "The sun never shone on a cause of greater worth . . . 'Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now." So powerful were his words, that in the colonies, people wanted to give credit for them to Franklin or Jefferson or Adams. Adams readily admitted that he wasn't capable of writing with such heart and strength.

Paine's words not only inspired, but they also angered virtually everyone in power at the time. Having gone back to England from where he had emigrated, he wrote "The Rights of Man," a pamphlet designed to rail against the criticism of the French Revolution. As a result, he became even more hated by the British monarchy and would have been arrested if he hadn't fled to France. The British tried him in absentia, anyway, and found him guilty. Then, despite his authorship of "The Rights of Man," he was arrested in France for not supporting the execution of Louis the XVI. While in prison, he worked on "The Age of Reason," a pamphlet that he stated was not against God but against the profitability of the church. As a result he was in deep trouble with both the politicians and the clerics. Politics and religion are the two things you don't discuss at dinner, but the fanatic Paine dove into both wherever his voice could be heard.

He might have lost his head to Monsieur l'Guillotine if not for the intervention in 1794 of James Monroe, America's Ambassador to France, but it was not until 1802, that he returned to America on the invitation of Thomas Jefferson. But America, the country he had worked so hard to create, did not welcome him. His great achievements were all but eradicated because of his anti-religious views. He was virtually friendless.

There is a wonderful play called "Tom Paine" written by Paul Foster that I and probably a few hundred other people have seen. I saw it twice, in fact, in the summer of 1970. In his experimental drama, Foster posits other reasons that people chose to hold Paine in distaste. He, like so many great writers, liked his liquor too much. He wasn't very good looking, and personal hygiene wasn't a priority for him. Also, unlike most of the other Founding Fathers, he was not a man of wealth. Paine was a bastard and the son of a bastard corset-maker. When upon returning to the country he had helped birth, he tried to vote and was summarily turned away. He died in 1809 in New York City and few people attended his funeral.

I am now back to my original thought: that perhaps the fanaticism of the tea party movement will eventually help shape a better America. It's kind of ironic to discuss them in the same essay with Thomas Paine, though, because way back in the 1790's, Paine endorsed, among other non-tea party things, a worldwide peace organization and a system of social security.

A caveat for tea party members and others who would change the world through fanaticism: As I mentioned before, Paine was found guilty in absentia for his treasonous behavior in England. When he died the British wanted his bones back. In the final speech in Foster's play, the audience is told, "with iron hammers they broke the stone above his head, and dug up his very bones and they shoveled them into a sack and they threw them aboard a ship bound for London to hang upside down before the jeering mobs. And when they were done, the raw stuff that moved the pen, were thrown into the street. And nobody knows where they are today. So went Tom Paine who shook continents awake."

Some information from USHISTORY.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment